TWO AND A HALF MONTHS AFTER PREVAILING IN COURT AGAINST FLIMSY HARASSMENT SUIT, WE POST A SMALL PORTION OF OUR DEFENSE AGAINST THE OUTRAGEOUS CLAIMS … DONE IN THE INTEREST OF TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY, which are SUMMED UP BY THE FIRST AMENDMENT

By DAN VALENTI

PLANET VALENTI News and Commentary

(FORTRESS OF SOLITUDE, MONDAY, SEPT. 24, 2012) — The First Amendment has been coming up a lot in our life of late. The most recent example came on Friday, when, on a radio/TV appearance with Shawn Serre of PCTV on “Good Morning, Pittsfield.” Serre asked THE PLANET our view on the wave of Muslim violence in protest to a bad film that denigrates the prophet Muhammed. I saw it was a First Amendment issue.

It’s been about two and a half months since Dan Valenti prevailed over Meredith Nilan in court, in a slam dunk ruling by Judge Mark Mason that we were well withing our rights to report and comment upon the incident involving Ms. Nilan in which she ran over and nearly killed pedestrian Peter Moore while driving her father’s SUV.

In that time, we have received numerous request for a posting of the briefs we filed. Agendas and schedules being what they are, THE PLANET has been unable to comply — until now. Here is a small part of the package we filed with the court to defend against the ridiculous claims of Ms. Nilan against Your Truly. We share for no other purpose than transparency of information.

In answering the fictitious harassment charges, we also knew what Ms. Nilan apparently didn’t: The suit would immediately trigger a First Amendment battle. We were more than happy to stand up for this most fundamental of American rights.

—– 00 —–

Massachusetts Trial Court District Court Department Central Berkshire (Pittsfield) Division

Meredith Nilan v. Daniel Valenti

Docket Number: 12 27RO 235

BRIEF OF DAN VALENTI

IN OPPOSITION TO CIVIL harassment prevention order under Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E

Rinaldo Del Gallo, III, Esq. for Dan Valenti PO Box 1081 Pittsfield, MA 01202-1082 (413) 445-6789

BBO 632880

1CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES …………………………………………………………………………………………..3 ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW……………………………………………………………………………5 STATEMENT OF THE CASE………………………………………………………………………………………..5 THE ARGUMENT ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18

There is no statutory provision under Mass. Gen. L. C. 258e §3(a) allowing a judge to proscribe or censure speech on the internet, apart from a generalized order not to abuse or harass defendant. ………………………………………………………………………….. 18

There is no “harassment” as defined under Mass. Gen. L. C. 258e§1………………. 20

This year’s case of O’brien v. Borowski limits what one may “fear” in order for there to be “harassment” and obtain a civil harassment protection order—one must be in fear of physical harm or physical damage to one’s property, and the words used must (1) “fighting words” or (2) “true threats.” ………………………………. 22

Ms. Nilan must show that Mr. Valenti’s speech consist of “fighting words” or “true threats,” and this she cannot do……………………………………………………………………….. 31

Mr. Valenti could not engage in fighting words because they would not incite an ordinary person to violence and there was no face to face confrontation. ……….. 33

Mr. Valenti did not engage in a “true threat” because he did not manifest an intent to visit physical harm to Ms. nilan or harm to her property. ……………………. 35

“True threats” must be objectively reasonable as a constitutional requirement and therefore statute suffers from overbreadth—O’Brien is wrong in this respect— the issue is reserved for U.S. Supreme Court. …………………………………………………… 42

Ms. Nilan cannot claim that because she feared from third parties because of Mr. Valenti’s coverage of her case, that she is entitled to relief. …………………………….. 47

Even, assuming arguendo, that Mr. Valenti has engaged in “fighting words” or “true threats,” the order is too broad and bans expression that is neither “true threats” or “fighting words” on Mr. Valenti’s blog. …………………………………………….. 50

There is a constitutional right to publish truthful information about other individuals about an area of public concern……………………………………………………… 52

The order constitutes an unconstitutional prior restraint and should not be continued………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 56

2

Cases

TTABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Alexander v. United States, 509 U.S. 544, 550 (1993)……. 57, 58 Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001)………………………………. 54, 55 Blue Canary Corp. v. City of Milwaukee, 251 F.3d 1121, 1123

(7th Cir. Wis. 2001) …………………………………………………………………………….. 60 Bobolas v. Does, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 110856 (D. Ariz.

Oct. 1, 2010)………………………………………………………………………………… 59, 60, 61 Bosley v. WildWetT.com, 2004 U.S. App. LEXIS 11028 (6th

Cir. Apr. 21, 2004)……………………………………………………………………………….. 59 Carroll v. Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175, 183 (1968)………………. 51 Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 20, 91 S. Ct. 1780, 29 L.

Ed. 2d 284 (1971)……………………………………………………………………………… 33, 34 Commonwealth v. A Juvenile, 368 Mass. 580 (Mass. 1975)……… 24 Commonwealth v. Chou, 433 Mass. 229, 236, 741 N.E.2d 17

(2001) ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 36, 37, 39 Commonwealth v. Gazzola, 17 Mass. L. Rep. 308 (Mass. Super.

Ct. 2004)……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 40 Commonwealth v. Welch, 444 Mass. 80, 94 (Mass. 2005)25, 26, 28,

40 Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975) ……………. 53 Doe v. Pulaski County Special Sch. Dist., 306 F.3d 616, 622

(8th Cir. 2002)………………………………………………………………………………………… 37 Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975)……………………….. 25 Johnson v. Campbell, 332 F.3d 199, 212 (3d Cir. 2003) ……….. 34 Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia, 435 U.S. 829

(1978)…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 55 Layshock v. Hermitage Sch. Dist., 496 F. Supp. 2d 587, 602

(W.D. Pa. 2007)………………………………………………………………………………………… 35 Merenda v. Tabor, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 63782 (M.D. Ga. May

7, 2012) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 34 Mortgage Specialists v. Implode-Explode Heavy Indus., 999

A.2d 184 (N.H. 2010);…………………………………………………………………………… 61 Near v. Minn., 283 U.S. 697, 713-714 (1931)…………………. 58, 61, 64 Neb. Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539, 598 (1976)………….. 59 Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U.S. 454, 462 (1907) …………………….. 59 Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Com. on Human Relations,

413 U.S. 376, 390 (1973),………………………………………………………………….. 60 3

Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co., 443 U.S. 97, 103 (1979) …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 54 Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4-5 (1949)……………………….. 49 The Florida Star v. B. J. F., 491 U.S. 524 (1989) ………………… 52

United States v. Fulmer, 108 F.3d 1486, 1492 (1st Cir. 1997)………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 36

United States v. Malik, 16 F.3d 45, 49 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 968, 115 S. Ct. 435, 130 L. Ed. 2d 347 (1994) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 36

United States v. White, 670 F.3d 498, 507 (4th Cir. Va. 2012)………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 42, 43 United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285(2008) …………………………. 24 United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285, 302 (2008) ……………. 25

Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 123 S. Ct. 1536, 155 L. Ed. 2d 535 (2003)……………………………………………………………………………………. 36

Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705, 708, 22 L. Ed. 2d 664, 89 S. Ct. 1399 (1969) ……………………………………………………………….. 39 Whitney v. Cal., 274 U.S. 357, 376 (1927) ………………………………….. 42

Statutes

Mass. Gen. L. c.258E………………………………………………………………………….. passim Other Authorities

Article 16 of the Massachusetts Constitution……………………………. 19 Treatises

Blackstone Commentaries ………………………………………………………………………….. 58 M. Nimmer, Nimmer on Freedom of Speech…………………………………………. 57

4

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether there is “harassment” as defined under Mass. Gen. L. C. 258e§1

Whether Ms. Nilan can show that Mr. Valenti’s speech consist of “fighting words” or “true threats”?

Whether Ms. Nilan can claim that because she feared from third parties because of Mr. Valenti’s coverage of her case, that she is entitled to relief?

Even, assuming arguendo, that Mr. Valenti engaged in “fighting words” or “true threats,” whether the order is too broad and bans expression that is neither on Mr. Valenti’s blog?

Whether there is a constitutional right to publish truthful information about other individuals about an area of public concern?

Whether the order constitutes an unconstitutional prior restraint?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On June 22, 2012, Meredith Nilan sought a civil harassment protection order pursuant to Mass. Gen. L. ch. 258E against journalist Dan Valenti for writings on his blog, PlanetValenti.com.1 She filed a

1

One page of PlanetValenti.com reads,

AN UNEXPURGATED RECREATION OF THE MEREDITH NILAN CASE, AND WHY IT STANDS AS AN INDICTMENT OF THE PITTSFIELD COURTS By DAN VALENTI PLANET VALENTI News and Commentary

5

(FORTRESS OF SOLITUDE, MONDAY, JAN. 23, 2012) — We The People have not rested our case in the Meredith-Cliff Nilan Hit-and-Run travesty. To be clear, the travesty lies the handling of the case, from the get go. If the driver is one of the Kapanskis, there’s hell to pay. If the driver is the daughter of one of the most arrogant and obnoxiously self-righteous of the GOBs, which is saying a heap, she skates.

We The People cannot let this finding stand without a thorough, honest, and objective investigation. Until then, the Pittsfield courts stand indicted on a charges of obstruction, malfeasance, and manipulation.

A SUMMATION OF A TRAVESTY OF JUSTICE — This happened, Then That Happened From all available evidence, here’s the play-by-play:

* It is the night of Dec. 8, around 8:15 p.m. Meredith Nilan, from all the available evidence and according to the police, has just finished partying at a BYP gathering famous not for “networking” but from drinking to excess. Not one BYP to date has publicly testified to what they saw of Nilan’s behavior that night. Almost all won’t even admit they were there. The photographic evidence, however, tell us some of the roster who were there at the Great Barrington hot spot. One attendee, who will not allow his or her name to be used, says Meredith Nilan drank heavily at the party. This is not been confirmed and must be considered hearsay, which, we remind our readers, doesn’t necessarily mean the information is not true. We must ask why the BYPs are so afraid to say anything. Could it be they know if they come out and tell the truth, the GOBs will punish them and their careers, locally, will be over? Many of the BYPs are, remember, professional and social climbers looking to get in on the gravy train.

* Meredith Nilan is driving on Winesap Road, near her home. A pedestrian is walk-jogging his dog on the opposite side of the road, heading in the same direction.

* Nilan’s car swerves. Clearly, she has lost control. Why? Too much alcohol? Texting? Yakking on a cell phone. Falling asleep at the wheel? Daydreaming? All of these? None of these? The vehicle, owned by and registered to her daddy, Clifford Nilan, crosses lanes crosses lanes and slams into the pedestrian.

* The impact is so great that, as revealed by the photographic evidence, the front grille is torn off, the hood is dented, and a fully delineated hole is created in the windshield just to the right of the driver. The hole is caused by the head of victim Peter Moore as it smashes through the safety glass. Incidentally, THE PLANET has seen a muscular wise guy take a baseball bat to a car windshield in anger. He needed several whacks with all his strength to even create hazing. More whacks produced a spider’s web cracking. Still more whacks finally broke through the glass. Try it today on your own vehicle. You’ll see how tough it is to break the glass, and yet — and yet — the force of the impact of Nilan’s vehicle and Moore’s head produced a hole in the windshield as if it came from a punch press. Excessive speed, perhaps?

THE EVIDENCE SUGGESTS: There’s No REASONABLE Way Meredith Nilan’s Story Can be Taken as Credible

* After surveying the damage to the vehicle, in photos that officials tried to suppress and that were first published by THE PLANET, there is no way one can reasonably believe the driver did not know she had hit a human being — not a “dog or a deer.”

* The driver does not stop, notify police, and wait for the police to arrive, as the law requires, despite the fact that a man is almost killed.

6

* The incident is hidden for almost a month, although THE PLANET first got wind of it maybe a week after it happened. Our first notice came in an e-mail from one of our spies. We made discreet inquiries. Miracle: Nobody knew, heard, saw, and was saying nothing. Nonetheless, we got enough of a confirmation to tell us there was truth to what we heard. Something had happened.

* The incident finally breaks. We learn that Cliff Nilan, and not Meredith, is the one who calls the cops. Why? Is she too impaired? She doesn’t report to the police until late the next morning, more than 15 hours after the accident. Her father, meanwhile, has refused to allow police to search the vehicle. He forces them to get a warrant.

* The recollection of the victim tells a story opposite of Nilan’s. The police investigation differs from the Nilan account on many crucial aspects. The physical evidence at the scene and on the Nilan vehicle support the claims of Moore and the police going against the alibis of Meredith Nilan, if we apply common sense and reason.

* Ah, the matter of the search warrant — ’tis a thing of beauty. Mysteriously, the Pittsfield police can’t get the courts in Pittsfield to issue a warrant. Was that because Cliffy Nilan knew they wouldn’t do so because of his connections there as the head of the Probation Department? Did he think police would give up or drop the case because it was politically too hot to handle?

* Police, though, don’t give up — to their eternal credit. THE PLANET gives the PPD its due. They get a warrant from the Southern Berkshire District Court.

* Pittsfield police charge Meredith Nilan with criminal misdemeanor counts. The courts are subject to a magistrate’s hearing.

Secret Hearing Bars Victim and His Lawyer; A Ringer Magistrate Railroads an Unbelievable Verdict

* The hearing is held in secret, Thursday, Jan. 12. THE PLANET is the only media source to investigate to give the public word of this.

* The magistrate has the option of opening or closing the hearing.

* The hearing is closed to the public. Let those damning words sink in for a moment. This of what they mean.

* The hearing is closed to the press.

* There is no independent witness to the proceedings. They can do what they damn well please, in short.

* The central Berkshire court brings in a ringer, Nathan Byrnes, an assistant clerk magistrate from Westfield, to hear the case. The defense claims Byrnes doesn’t know ANY of the people involved, which is a claim laughable on its surface, given the cozy nature of the court system. It’s not like Westfield is on the Dark Side of the Moon.

* The victim, Peter Moore, is not allowed to attend the hearing. * The victim’s lawyer, by his own testimony, is not allowed to attend the hearing. * Meredith Nilan’s lawyer, Tim Shugrue, Is allowed to attend and present evidence.

7

supporting affidavit also dated June 22, 2012, herein after “Nilan Affidavit,” cataloging her misgivings with PlanetValenti.com.

The civil harassment statute, codified in Mass. Gen. L. c.258E, § 1 et seq., is a new statute and was enacted into law in 2010. As such, much of the law is still in a stage of development. Civil harassment restraining orders were created based upon a perceived “loophole” in the restraining order law which only applied to members that were in a dating relationship, living in the same household, or related to a certain degree. “Chapter 258E was enacted in 2010 to allow individuals to obtain civil restraining orders against persons who are not family or household members [as with a typical chapter 209A restraining order], and to make the violation of those orders punishable as a

* The magistrate finds that there is insufficient evidence for the case to go to trial. This incredulous finding serves as a credible indictment of the Pittsfield District Court as an institution controlled by corrupt officials who have established two sets of laws: One for themselves and the GOBs, and one for everyone else, that is, the unwashed masses who don’t have favored status, as Meredith Nilan apparently does.

* Despite the fact that there is no independent confirmation of what went on in the hearing, the Boring Broadsheet — a newspaper once known as The Berkshire Eagle — dutifully prints the story of the finding. No harm, no foul. Oops. Sorry, Peter Moore. Get over it, big guy. The BB story — which runs without a byline, that is, anonymously — only quotes Shugrue. It takes his account as whole cloth, including his spurious claim that a full evidential hearing was held. That turns out to be a false claim, since the other side in the case was not allowed to present or attend. The BB later beings a more responsible approach to its coverage, forced into doing to by public outrage and the pressure of this website’s coverage.

8

crime.” O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 419 (Mass. 2012) (bracketed material added).

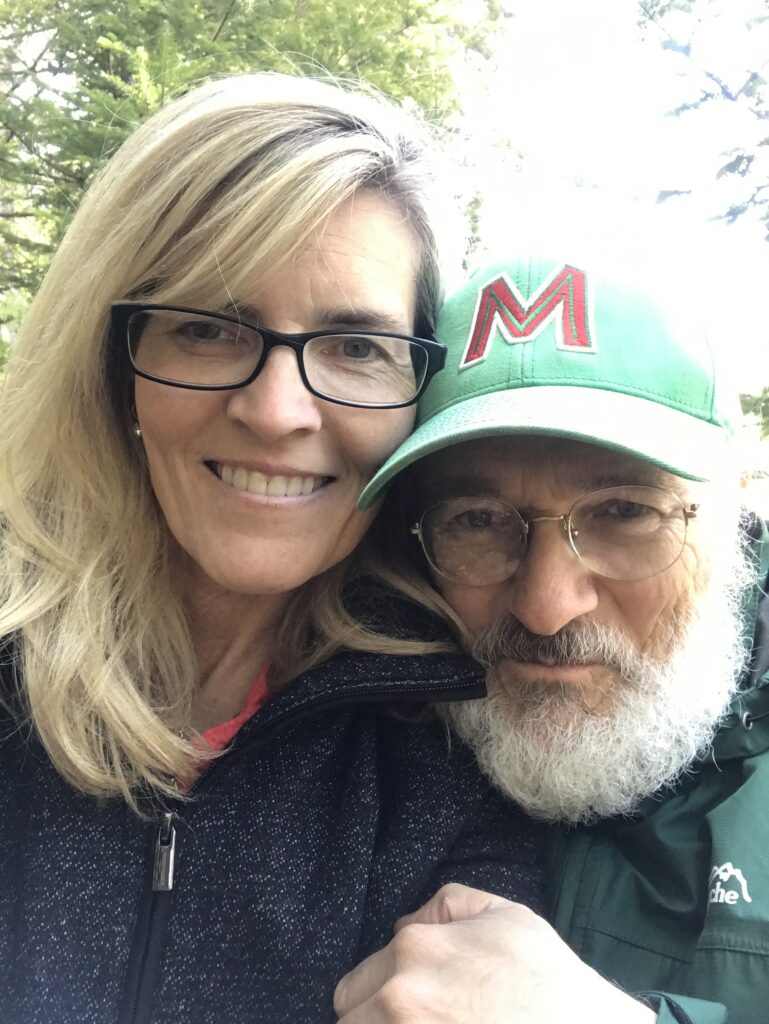

Dan Valenti is a journalist of considerable distinction: He has a Master’s degree (M.A.) in journalism, S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University (1975), one of the top journalism schools in the country. He has worked for and/or written for numerous newspapers, including the Syracuse, N.Y., Post-Standard, the Pennsylvania Times Leader, the Berkshire Eagle, and the Pittsfield Gazette. His work has been published in many newspapers and magazines across the country, including the SF Chronicle, the Boston papers, and many others. He broadcasted on the radio for two years in the mid- 80s at WUPE and WUHN (Pittsfield, Mass.), then 14 years (1992-2006) at WBRK and WRCZ (Pittsfield). He has written and edited numerous books, from major publishers such as Viking Penguin and Bantam to small literary presses. His work has been reviewed in many publications, including the New York Times Book Review. He has been a member of the English Department faculty at Berkshire Community College for 20 years (1992-2012), where he teaches composition and

writing. BCC honored him for his service in May of

9

this year at a recognition dinner at Wahconah Country Club in Dalton, Mass. Mr. Valenti also taught for two years at LeMoyne College, Syracuse, N.Y., teaching expository writing and communications. His work has received numerous awards and honors. July 5th Affidavit of Dan Valenti, p. 4-5, herein after “Valenti Affidavit.”

Dan Valenti has a blog, PlanetValenti.com, to which Ms. Nilan took great offense regarding an automobile accident in which Ms. Nilan was involved. The gist of her complaint is that Mr. Valenti unfairly portrayed her as a drunk driver who left the scene of an accident, and that his coverage on her on his blog was full of lies, exaggerations, and distortions. In an affidavit dated June 22, 2012, Ms. Nilan advanced a number of theories for issuance of a criminal harassment prevention order, to which Mr. Valenti wrote a responsive affidavit dated and filed on July 5, 2012. It is interesting to note what is not stated in Ms. Nilan’s affidavit:

1. There is no claim that Mr. Valenti has ever met Ms. Nilan or has in way had a face-to-face meeting.

10

2. There is no claim that Mr. Valenti has ever physically threatened her.

3. There is no claim that Mr. Valenti has solicited others to harm her.

Because it is difficult to articulate a single theory why Ms. Nilan believes a restraining order should issue, or what is background information or what her asserted basis for a harassment prevention order, a best effort will be made to summarize her arguments.

• First,Ms.Nilanappearstoassertinher affidavit in numerous places that Mr. Valenti has slandered her in a “regular and vicious attack on [her] reputation.” Nilan Affidavit at 1. Her affidavit is suffused with statements that Mr. Valenti has somehow lied and sensationalized facts, yet fails to identify a single assertion of fact of Mr. Valenti’s that is supposed to be a lie, save for one; she accuses Mr. Valenti of falsely “representing [her] as a drunk driver who ran a man and left him to die—all false.” Id. As to

11

what particular words in the PlantetValenti.com blog that were “lies,” Ms. Nilan does not mention. In his responsive affidavit, Mr. Valenti asserts that he was not libelous, and his blog contained fair commentary.

• Second,Ms.NilansuggeststhatMr.Valentihas been otherwise unfair in his coverage (in addition to her allegations that Mr. Valenti lied). She states Mr. Valenti wrote “sensational interpretations,” such as by saying that Ms. Nilan “‘left a man to die’ while the case was unresolved.” She also finds unfair that Mr. Valenti continued to assert that Ms. Nilan was guilty of a hit and run when it has “since been adjudicated and the charge dismissed.” Mr. Valenti asserts in his responsive affidavit that his blog met high journalistic standards. He also asserts that the damage to her automobile was consistent with a hit and run accident. On page 11 of his July 5th affidavit, Valenti states, “The photos [of Nilan’s car after the accident] clearly show heavy front-end damage and a head-sized

12

hole in the windshield near the driver’s position — damage that would be consistent with hitting a human being.”2

• Third—andthisisthebestinterpretationthat can be rendered—Ms. Nilan appears to be arguing that by printing “lies” and “sensational” accounts and “innuendos” and otherwise being unfair in his coverage of her case, Mr. Valenti is somehow encouraging others to be violent towards her by getting members of the public to unfairly hate her and become riled up. This will be called a “listener reaction” argument. “Mr. Valenti’s continued vitriol and his repeated inclination to print lies and sensationalize every aspect of my case has made me fear for my personal safety.” Nilan Affidavit at 1. “His repeated claim that ‘the fix was in on my case’ make me fear vigilante justice.” Id. at 2. She adds, “I fear for my

Ms. Nilan repeatedly states that Mr. Valenti stated that she was drunk when she hit a pedestrian—this is not technically correct. Mr. Valenti only suggests this is a strong possibility given (1) the loss of control of the vehicle, and (2) the fact that Ms. Nilan had been coming from a party where there had been much drinking. PlanetValenti read, “Nilan’s car swerves. Clearly, she has lost control. Why? Too much alcohol? Texting? Yakking on a cell phone? Falling asleep at the wheel? Daydreaming? All of these? None of these? The vehicle, owned by and registered to her daddy, Clifford Nilan, crosses lanes crosses lanes and slams into the pedestrian.” Valenti continues to use this approach of objectively

13

2

safety from these constant actions that I feel represent cyberbullying and harassment.” Id. She states that she “recently received death threats which [she] believes are related to Mr. Valenti’s words and this has only heightened my stress level.” Id.

• Fourth,butrelatedtothethirdconcern,is that Mr. Valenti has published personal information about Ms. Nilan, including where she works and the street she lives on. Thus, appears to be the argument, the venom for Ms. Nilan coupled with identifying information such as her likeness, her place of work, and the street she lives on, places her at great physical risk.

• Fifth,thereseemstobeanargument,that apart from fear of her own safety, that since readers of Dan Valenti’s log might “boycott [her] work, or suggest that she should be fired from her place of employment, or “march en masse on [her] street,” that this is also grounds for a civil harassment protection order to issue. Nilan Affidavit at 1.

14

• Sixth—andthisisthebestthatcanbemadeof the theory which is not articulated—is what seems to be an invasion of privacy argument. Ms. Nilan accuses Mr. Valenti, in his blogging efforts, of contacting “police, court officials, law makers, and business associates asking them to weigh-in on my case . . .” “He has printed photos taken without my permission from the inside of [her] garage, as well as pictures of my neighborhood, and of me.”

While contacting police, courts officials, lawmakers, and business associates is a common journalist practice, Mr. Valenti states in his affidavit,

“To the best of my knowledge, I did not directly contact in a substantive manner such people that Ms. Nilan claims. I therefore could not have shared my ‘interpretation’ with them (police, court officials, lawmakers, her work mates). As I have stated previously, the story largely came to me. To the best of my recollection, I did directly contact two people: (a) Mr. Alfred ‘Alf’ Barbalunga, chairman of the Pittsfield school committee and probation officer of Southern Berkshire District Court, who was pictured in a photograph taken with Ms. Nilan on the evening of Dec. 8 at the BYP party at Allium’s restaurant, and (b) Ms.

15

Ashley Sulock, PR director for the Berkshire Chamber of Commerce.”

Nor does Ms. Nilan claim that she has ever met Dan Valenti.

• Seventh,thereNilancomplainsthatMr.Valenti “made one wish that there was a place people could be ‘put down.’” This is the only thing that could remotely be labeled a “physical threat.” Mr. Valenti responded in his affidavit that Mr. Nilan “brings up a phrase that was clearly meant to be figurative.” Valenti affidavit at 15. Mr. Valenti maintains this is hyperbole.

On June 27, 2012, after an ex-parte hearing, District Court Judge Bethzaida Sanabria-Vega issued a temporary order of harassment prevention pursuant to Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §5 (which provides for the issuance of temporary orders). Included were the customary issuance of an order to stay 100 yards from the plaintiff and an order to stay away from the plaintiff’s work and residence. But in addition to these usual provisions, in Section 3 of the order

16

there were the additional provisions that Mr. Valenti was . . .

“ordered to remove any and all information referring to the Plaintiff [Ms. Nilan] from any and all websites, blogs, etc.”

Mr. Valenti’s interpretation of this order is not only must he pull the material on the website down before it was reviewed by the court (a species of prior restraint), but that he must also not publish any future articles mentioning Meredith Nilan (the acme of prior restraint). In his affidavit, Mr. Valenti has stated that

“the prior restraint has caused me not to add further commentary on my website, Planet Valenti, including this case. This ruling as I understand it prevents me from publishing new articles in any way mentioning her. The judge’s order required me to pull content from my website, material already published, as if the Nilan-Moore case didn’t happen. The judge’s actions in allowing a temporary restraining order violate my First Amendment rights under freedom of speech as a citizen and freedom of the press as a journalist.”

Valenti Affidavit at p.17.

17

THE ARGUMENT

Pursuant to Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §3 (a),

(a) A person suffering from harassment3 may file a complaint in the appropriate court requesting protection from such harassment. A person may petition the court under this chapter for an order that the defendant:

(i) refrain from abusing or harassing the plaintiff, whether the defendant is an adult or minor;

(ii) refrain from contacting the plaintiff, unless authorized by the court, whether the defendant is an adult or minor;

(iii) remain away from the plaintiff’s household or workplace, whether the defendant is an adult or minor; and

(iv) pay the plaintiff monetary compensation for the losses suffered as a direct result of the harassment; provided, however, that compensatory damages shall include, but shall not be limited to, loss of earnings, out-of-pocket losses for injuries sustained or property damaged, cost of replacement of locks, medical expenses, cost for obtaining an unlisted phone number and reasonable attorney’s fees.

There is no statutory provision under Mass. Gen. L. C. 258e §3(a) allowing a judge to proscribe or censure speech on the internet, apart from a generalized order not to abuse or harass defendant.

3 It is worthy of note that while a party maybe ordered to desist from abusing a plaintiff, “harassment” is the sine qua non for the issuance of a harassment protection order—if there has been no harassment, there is no legal justification for issuance of the order.

18

While this case raises many issues regarding the free speech provisions of the First Amendment of the United States and Article 16 of the Massachusetts Constitution, it also raises a much more pedestrian issue: Where in Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §3(a), or in any other part of Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E for that matter, does it authorize a court to order a defendant to remove all material from a blog or website mentioning a plaintiff? There is no such provision. Granted, Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §3(a)(i) allows a judge to issue an order to “refrain from abusing or harassing the plaintiff” similar to the “no abuse” counterpart to a restraining order, but this not a license to start censuring speech on the Internet. Mr. Valenti argues that in addition to the order’s provisions (or any future such order) to remove all articles or comments referring in any way to Meredith Nilan as being in violation of the free speech provisions of the Massachusetts and Federal constitutions, the remedy is not a remedy as provided in Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E and is therefore without legal justification. When the legislature has clearly and unmistakably stated all the remedies afforded under a statute, it is not the

19

province of courts to engraft new ones. Inclusio unius est exclusio alterius.4

There is no “harassment” as defined under Mass. Gen. L. C. 258e§1

The next order of inquiry is whether Mr. Valenti has “harassed” Ms. Nilan so as to afford her any remedy under Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §3(a), for it is only a person suffering “harassment” that may file a complaint. Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §1 provides several definitions useful in interpreting Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §3(a):

Section 1. As used in this chapter the following words shall, unless the context clearly requires otherwise, have the following meanings:

“Abuse”, attempting to cause or causing physical harm to another or placing another in fear of imminent serious physical harm.

“Harassment”, (i) 3 or more acts of willful and malicious conduct aimed at a specific person committed with the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property5 and that does in fact cause fear,

4 The inclusion of one is the exclusion of the other. 5 There is no claim in the Nilan Affidavit that Mr. Valenti abused her or damaged her property.

20

intimidation, abuse or damage to property; or (ii) an act that:

(A) by force, threat or duress causes another to involuntarily engage in sexual relations; or

(B) constitutes a violation of section 13B, 13F, 13H, 22, 22A, 23, 24, 24B, 26C, 43 or 43A of chapter 265 or section 3 of chapter 272. . . .

“Malicious”, characterized by cruelty, hostility or revenge.

It is worthy of note that while “harassment” is defined, the statute does not specify just what the plaintiff might “fear” or be “intimidated” about that is cause to trigger “harassment.” There is a subject— the defendant who causes the fear or intimidation. There is an object—the plaintiff who is at the receiving end of the fear or intimidation. But there is no modifying prepositional phrase of “intimidation” or “fear.” If “fear” of anything or “intimidation” about anything could constitute “harassment,” any speech that is critical of another could be considered “harassment” since people often fear criticism or otherwise being portrayed in an unfavorable likeness, and might be intimidated that such criticism might

repeat itself. Thus, without some type of limiting

21

definition of “fear” or “intimidation,” the statute is unconstitutionally broad.

This year’s case of O’brien v. Borowski limits what one may “fear” in order for there to be “harassment” and obtain a civil harassment protection order—one must be in fear of physical harm or physical damage to one’s property, and the words used must (1) “fighting words” or (2) “true threats.”

The recently decided case of O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415 (Mass. 2012) is important because it was just held that Massachusetts civil harassment statute is not unconstitutionally overly broad. Id. at 416. O’Brien is a somewhat unusual case in that it was moot when the case was decided, but because it “raise[d] issues of public importance regarding the

constitutionality of a recently will likely arise again but, if of mootness, evade review,” id. heard on the overbreadth issue.

enacted statute that [dismissed] on grounds at 551, the case was

In order to understand the this case, it is important to understand overbreadth jurisprudence under the First Amendment. In some cases a statute can be challenged if it jeopardizes

too much speech so as to strike the entire statute—an

22

effect of O’Brien in

“overbreadth” or “facial” challenge. Unlike other constitutional challenges where one has to show that the Constitution has been violated as pertains to their particular case (as a fundamental requirement of standing), the First Amendment free speech provisions is so important that an overbreadth challenge may even be brought by a party who did not actually engage in the protected speech and whose own speech may be unprotected. One would ordinarily lacking standing by arguing that while their constitutional rights have not been violated, the law (be it or a statute, ordinance, or regulation) violates the constitutional rights of others. But a person that did not personally have their First Amendment free speech rights violated by a statue may argue that, nonetheless, so much legitimate speech is imperiled by a statute that the statute is “substantially” overly broad because it has too much of a chilling effect, and that the statute must fall. “[I]f a law is found deficient as unconstitutionally overbroad in its potential application to protected speech, it may not be applied even to the person raising the challenge though that person’s speech is arguably unprotected by

23

the First Amendment.” Commonwealth v. A Juvenile, 368 Mass. 580, 585 (Mass. 1975).

The amount of constitutionally protected statute injured by a law must be more than a hypothetical possibility—a substantial amount of protected speech must be imperiled. United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285, 292 (2008)( “According to our First Amendment overbreadth doctrine, a statute is facially invalid if it prohibits a substantial amount of protected speech.”); See generally Bulldog Investors Gen. Partnership v. Secretary of the Commonwealth, 460 Mass. 647, 676-677, 953 N.E.2d 691 (2011) for a good description of the overbreadth doctrine.

“Overbreadth” is considered “strong medicine,” so very often a court will be reluctant to invalidate an entire statute. Nonetheless, sometimes a statute may not proscribe so much speech as to render their entire statute invalid on a facial or overbreadth challenge, but might be invalid “as applied” to a given situation or class of speech. For instance, a child pornography statute might not proscribe so much speech so as to be “substantially” overly broad so as to completely invalidate the statute, but might be unconstitutional

as applied by outlawing “documentary footage of

24

atrocities being committed in foreign countries, such as soldiers raping young children.” United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285, 302 (2008).

When a statute is overly broad, it is sometimes stricken down entirely. For instance, in Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975), a local ordinance in Florida restricting the ability of a drive-in movie theater to show films containing nudity was invalidated in its entirety; the court did not engraft a judicially created limitation such as that the ordinance would only apply to obscenity. See Commonwealth v. Welch, 444 Mass. 80, 94 (Mass. 2005) for a recitation of a number of cases where statutes or ordinances were stricken that regulated putative offensive or harassing speech. The O’Brien court did not follow such an approach.

Sometimes when courts are faced with an overbreadth challenge, a court will leave parts of a statute intact, while invalidating other parts of the statute that pertain to regulating speech or expression. For instance, in Commonwealth v. A Juvenile, 368 Mass. 580, 587 (Mass. 1975), as to the “disorderly conduct” statute as codified in ALM GL ch.

272, § 53, it was ruled that “the offense of being a

25

disorderly person in so far as it encompasses speech or expressive conduct is not sufficiently narrowly and precisely drawn to ensure that it reach only that speech which the State has a justifiable and compelling interest in regulating, and is therefore overbroad.” “However, [the court also] conclude[d] that as reaching to conduct (other than expressive conduct), the § 53 ‘idle and disorderly persons’ provision is neither unconstitutionally overbroad nor vague.” Id. In O’Brien, no part of the civil harassment protection statute was stricken as in Commonwealth v. A Juvenile.

Sometimes a court when confronted with an overbreadth challenge will rule that a statute that affects speech and other forms of expression was given a sufficiently narrow meaning by the legislature so as not be to be either overly broad or vague. For instance, in 2000, the Massachusetts criminal harassment statute was enacted. Its constitutionality under the free speech provisions of the US Constitution’s First Amendment or Article 16 of the Massachusetts Constitution was called into question for overbreadth in Commonwealth v. Welch, 444 Mass.

26

80, 97 (Mass. 2005). The Welch court noted, in review

of a

statute then only five years old, that

“States, however, have construed their statutes that proscribe harassing conduct or speech as constitutionally permissible. Most commonly, statutes have been upheld that contain some combination of the following limiting characteristics: a “willful,” “malicious,” or specific intent element; a requirement that the conduct be “directed at” an individual; a reasonable person standard; a statutory limitation that the conduct have “no legitimate purpose”; and a savings clause excluding from the statute’s reach constitutionally protected activity or communication.”

The Welch court recited numerous examples of such cases where statutes were not stricken but saved by narrowing constructions. The Welch court followed this approach by not striking the entire criminal harassment statute as overly broad or vague, but instead gave the Massachusetts criminal harassment statute a narrow interpretation. This was based upon a permissible interpretation of the narrow intent of the legislature to make the statue pass constitutional muster. Id. at 96.6 While it was true that the

6 Courts are reluctant to save a statute from a constitutional infirmity with a narrowing interpretation of the statutory language that makes it constitutional but is at odds with the intent of the legislature.

27

“Massachusetts criminal harassment statute lacks a savings clause or other provision that restricts punishable conduct to that which is constitutionally unprotected,” Welch, 444 Mass. at 99, and while “[s]imilarly, it contains no express limitation to fighting words,” id., the court held:

“Nonetheless, we believe the Legislature, in carefully crafting the statute, intended the statute be applied solely to constitutionally unprotected speech. Any attempt to punish an individual for speech not encompassed within the “fighting words” doctrine (or within any other constitutionally unprotected category of speech) would of course offend our Federal and State Constitutions.”

Commonwealth v. Welch, 444 Mass. 80, 99 (Mass. 2005) “In Welch, [the Supreme Judicial Court] considered the constitutionality of the criminal harassment statute, G. L. c. 265, § 43A, and concluded that, while the harassing conduct punishable under the statute may include harassing speech, the statute passed constitutional muster because it was carefully crafted by the Legislature to apply “solely to constitutionally unprotected speech.’” O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 420 (Mass. 2012).

28

The O’Brien court followed the approach in Welch by narrowing just what might be “feared” or be “intimidated” about when one is “harassed” as defined under the civil harassment protection statute so as to save it from overbreadth. In O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 421 (Mass. 2012), the court had to be decided whether the civil harassment statute passed in 2010 was facially invalid for overbreadth. The O’Brien court, while noting distinct differences in the civil harassment and criminal harassment statutes, nonetheless followed the Welch court’s lead and “conclude[d] that the Legislature crafted the civil harassment act, G. L. c. 258E, with the intent that the definition of harassment exclude constitutionally protected speech, and [interpreted] G. L. c. 258E to effectuate that legislative intent.” O’Brien at 425.

The O’Brien court stated that what comes in the ambit of the civil harassment statute are “fighting words” and “true threats.” If “harassment” is defined in Mass. G. L. c. 258E(1) as “or more acts of willful and malicious conduct aimed at a specific person committed with the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse,” and the “fear” caused could become fear of

anything, the statute would be patently overly broad,

29

if not also vague. If fear could mean “fear of economic loss, of unfavorable publicity, or of defeat at the ballot box,” as the O’Brien court gave as examples, id. at 427 (emphasis supplied), the statue would encompass Mr. Valenti’s blog, and would clearly be unconstitutional. But the O’Brien court did not allow “fear” to be fear of anything. It certainly did not allow “fear” or “intimidation” to be predicated on fear of unfavorable publicity which form the basis of Ms. Nilan’s complaint. The O’Brien court ruled:

We interpret the word “fear” in G. L. c. 258E, § 1, to mean fear of physical harm or fear of physical damage to property. With that narrowed construction, we conclude that the civil harassment act, G. L. c. 258E, is not constitutionally overbroad because it limits the scope of prohibited speech to constitutionally unprotected “true threats” and “fighting words.” With that narrowed construction, we conclude that the civil harassment act, G. L. c. 258E, is not constitutionally overbroad because it limits the scope of prohibited speech to constitutionally unprotected “true threats” and “fighting words.”

O’Brien at 430 (emphasis supplied). This proves fatal to Ms. Nilan’s case because she

does not allege, not could she allege, that Mr.

Valenti put her in fear of physical harm or fear of

damage to her property, let alone, as the statute

30

(Mass. Gen. L. c. 253E §1 requires in its definition of harassment) that Mr. Valenti engaged in “willful and malicious conduct” that was done “with the intent to cause fear [or] intimidation.” Ms. Nilan could not show that this happened once, let alone three times as required in Mass. Gen. L. c. 253E §1’s definition of harassment.

Even it were true that Mr. Valenti urged that Ms. Nilan “be fired or that they boycott [her] work or march en masse on [her] street” as stated in Ms. Nilan’s affidavit, even if it true that Mr. Valenti asked his readers to “weight in on [her] case” as stated in her affidavit, or even if it were true that Mr. Valenti helped organize a benefit for accident victim and in doing so “represented [Ms. Nilan] as a drunk driver who ran a man down and left him to die” as stated in her affidavit, or even if photos to her car were published as stated in her affidavit, or even if the street she lives on or where she works was published in on his website, this is not a physical threat to person or property as required by O’Brien.

Ms. Nilan must show that Mr. Valenti’s speech consist of “fighting words” or “true threats,” and this she cannot do.

31

So what is the scope of the civil harassment statute? While the criminal harassment statute was limited to “fighting words” in Welch, the civil harassment statute was limited to “fighting words” and “true threats,” reasoning that . . .

Because the definition of “civil harassment” is substantially broader than the definition of “fighting words,” we discern no legislative intent to confine the meaning of harassment to fighting words, but we do discern an intent to confine the meaning of harassment to either fighting words or “true threats.”

O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 425 (Mass. 2012). In footnote 7, in obiter dicta,7 the court opined that they were wrong in Welch and should have concluded that the criminal harassment statute should have been interpreted to include “fighting words” and “true threats.” Id. at 425 n.7. The O’Brien court reasoned:

Because a “true threat” need not produce an imminent fear of harm, we erred in concluding that “true threats” analysis did

7 It was clearly dicta because the criminal harassment statue was not in any way a subject of litigation.

32

not apply to criminal harassment. Welch, supra. Having unnecessarily excluded “true threats” from our constitutional analysis, we similarly erred in concluding that the criminal harassment statute was limited in its reach to “fighting words” rather than both “fighting words” and “true threats.”

O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 425 n.7 (Mass. 2012).

Mr. Valenti could not engage in fighting words because they would not incite an ordinary person to violence and there was no face to face confrontation.

The “fighting words” exception to the First Amendment is limited to words that are likely to provoke a fight and a breach of the peace because one person would be likely to strike another. “Fighting words” constitute face-to-face personal insults that are so personally abusive that they are plainly “likely to provoke a violent reaction and cause a breach of the peace.” See Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 20, 91 S. Ct. 1780, 29 L. Ed. 2d 284 (1971) (fighting words are “personally abusive epithets which, when addressed to the ordinary citizen, are, as a matter of common knowledge, inherently likely to provoke violent reaction”); Chaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, supra at 572 (fighting words are words 33

whose “very utterance . . . tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace”); Commonwealth v. A Juvenile, supra at 591. Fighting words thus have two components: they must be a direct personal insult addressed to a person, and they must be inherently likely to provoke violence. As such, the fighting words exception is “an extremely narrow one.” Johnson v. Campbell, 332 F.3d 199, 212 (3d Cir. 2003).

“Fighting words” inherently require a face-to- face situation because the underlying theory is that they would cause an immediate breech of the piece. “Fighting words situations involved face to face encounters.” Barron and Dienes, First Amendment Law (in a Nutshell)(4th ed.), p.82. “Fighting words require face to face confrontation.” Merenda v. Tabor, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 63782 (M.D. Ga. May 7, 2012).

Since there is no face-to-face confrontation, postings on the Internet (such as Mr. Valenti’s blog at PlanetValenti.com) cannot be considered “fighting words.” For instance, it has been held that “[a] ‘MySpace’ internet page is not outside of the protections of the First Amendment under the fighting

34

words doctrine because there is simply no in-person confrontation in cyberspace such that physical violence is likely to be instigated.” Layshock v. Hermitage Sch. Dist., 496 F. Supp. 2d 587, 602 (W.D. Pa. 2007).

As stated in Mr. Valenti’s Affidavit on page 2, “To this date, I have never met her, talked with her, been near her, contacted or attempted to contact her, or spoken to Meredith Nilan.” Nor does Ms. Nilan claim (nor could she claim) that there was a face-to- face encounter. Moreover, even his if he said statements in his blog to Ms. Nilan’s face, they could not be considered so vituperative and utterly without value so as to cause an immediate breach of the peace.

Mr. Valenti did not engage in a “true threat” because he did not manifest an intent to visit physical harm to Ms. Nilan or harm to her property.

Once it has been determined that words do not constitute “fighting words,” the only category of speech that falls within the civil harassment statute

are “true threats.” The O’Brien court outlined just 35

what is a “true threat” so as to fall within the civil harassment protection statute:

True threats. In Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 123 S. Ct. 1536, 155 L. Ed. 2d 535 (2003) (Black), the Supreme Court defined true threats:

‘True threats’ encompass those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals. . . . The speaker need not actually intend to carry out the threat. Rather, a prohibition on true threats ‘protect[s] individuals from the fear of violence’ and ‘from the disruption that fear engenders,’ in addition to protecting people ‘from the possibility that the threatened violence will occur.'” . . .

The term ‘true threat’ has been adopted to help distinguish between words that literally threaten but have an expressive purpose such as political hyperbole, and words that are intended to place the target of the threat in fear, whether the threat is veiled or explicit.” Commonwealth v. Chou, 433 Mass. 229, 236, 741 N.E.2d 17 (2001) (Chou).

A true threat does not require “an explicit statement of an intention to harm the victim as long as circumstances support the victim’s fearful or apprehensive response.” Id. at 234. See United States v. Fulmer, 108 F.3d 1486, 1492 (1st Cir. 1997) (“use of ambiguous language does not preclude a statement from being a threat”); United States v. Malik, 16 F.3d 45, 49 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 968, 115 S. Ct. 435, 130 L. Ed. 2d 347 (1994) (“absence of explicitly threatening language does not preclude the finding of a threat”). Nor need

36

a true threat threaten imminent harm; sexually explicit or aggressive language “directed at and received by an identified victim may be threatening, notwithstanding the lack of evidence that the threat will be immediately followed by actual violence or the use of physical force.” Chou, supra at 235. See Black, supra at 359-360 (defining true threats without imminence requirement); Doe v. Pulaski County Special Sch. Dist., 306 F.3d 616, 622 (8th Cir. 2002) (“serious expression of an intent to cause a present or future harm” is true threat).

For example, in Chou, supra at 230-231, the defendant produced flyers with the word “MISSING” printed in large type across the top, beneath which was a photograph of a former girl friend who had broken up with him and offensive sexual remarks about her, and then hung the flyers in several places in her high school. He was convicted under G. L. c. 272, § 53, id. at 230, which criminally punishes “persons who with offensive and disorderly acts or language accost or annoy persons of the opposite sex.” We concluded that the defendant’s criminal conviction for this communication did not violate the First Amendment because it was a true threat that “had no expressive purpose but was, instead, intended to ‘get back’ at the victim by placing her in fear that she might suffer some sexual harm or wind up among the ‘missing.'” Id. at 237. We recognized that “[s]exually explicit language, when directed at particular individuals in settings in which such communications are inappropriate and likely to cause severe distress, may be inherently threatening.” Id. at 234.

In Black, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Virginia law that prohibited the burning of a cross with intent to intimidate, concluding that, in view of the Ku Klux Klan’s “long and pernicious history” of using the burning of

37

a cross “as a signal of impending violence,” it constituted a true threat, unprotected by the First Amendment, when committed with an intent to intimidate. Black, supra at 363.n6 The Supreme Court noted that “[i]ntimidation in the constitutionally proscribable sense of the word is a type of true threat, where a speaker directs a threat to a person or group of persons with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.” Id. at 360. Taken together, Chou and Black demonstrate that the “true threat” doctrine applies not only to direct threats of imminent physical harm, but to words or actions that — taking into account the context in which they arise — cause the victim to fear such harm now or in the future and evince intent on the part of the speaker or actor to cause such fear.

O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 423-425 (Mass. 2012)(emphasis supplied). The gist of a “true threat” is that someone directly or unmistakably suggests that they will visit harm to another’s person or property.

Nowhere is it ever alleged by Ms. Nilan that Mr. Valenti “communicated a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence” so as to constitute a “true threat.” Not only is there no “direct” threat, but there is not an “implied” threat as by burning a cross across from an Afro-American’s house as described in Black, or by placing “Missing”

signs of a person as in Chou to suggest the person 38

will soon be missing. Ms. Nilan could not possibly suggest that she fears physical harm to her person or her property from Mr. Valenti.

Ms. Nilan complains that Mr. Valenti stated in his blog that Ms. Nilan “made one wish that there was a place people could be ‘put down.’” Nilan Affidavit at p.1. Mr. Valenti responds that she “brings up a phrase that was clearly meant to be figurative.” Valenti Affidavit at p.15. Political hyperbole that a reasonable person would not consider as a genuine threat cannot constitute a “true threat.” Commonwealth v. Chou, 433 Mass. 229, 236, 741 N.E.2d 17 (2001)( The term ‘true threat’ has been adopted to help distinguish between words that literally threaten but have an expressive purpose such as political hyperbole, and words that are intended to place the target of the threat in fear, whether the threat is veiled or explicit.”; Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705, 708, 22 L. Ed. 2d 664, 89 S. Ct. 1399 (1969)(the defendant’s statement that “if they ever make me carry a rifle, the first man I want to get in my sights is LBJ” was not held to be a “true threat” punishable as such but was instead “political

hyperbole” which was not a crime at all); Commonwealth 39

v. Gazzola, 17 Mass. L. Rep. 308 (Mass. Super. Ct. 2004).

Incidentally, even assuming, arguendo, the ridiculous proposition that Mr. Valenti’s comment that Ms. Nilan “made one wish that there was a place people could be ‘put down’ was not hyperbole or figurative, it would only constitute one instance of a “true threat” when three (3) incidents are needed by the civil harassment protection statute. O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 420 (Mass. 2012). Harassment,” as defined in Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §1 is defined as “3 or more acts of willful and malicious conduct aimed at a specific person committed with the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property.” A single entry on a blog would only constitute one.

The O’Brien court distinguished between the types of threats in criminal harassment and civil harassment protection:

Both civil and criminal harassment require proof of three or more acts of wilful and malicious conduct aimed at a specific person. See Commonwealth v. Welch, 444 Mass. 80, 89, 825 N.E.2d 1005 (2005) (Welch) (“phrase ‘pattern of conduct or series of acts’ [in G. L. c. 265, § 43A,] requires the

40

Commonwealth to prove three or more incidents of harassment”). But the definitions of civil and criminal harassment differ in three respects. First, there are two layers of intent required to prove civil harassment under c. 258E: the acts of harassment must be wilful and “[m]alicious,” the latter defined as “characterized by cruelty, hostility or revenge,” and they must be committed with “the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property.” G. L. c. 258E, § 1. Only the first layer of intent is required for criminal harassment under c. 265, § 43A. Second, the multiple acts of civil harassment must “in fact cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property,” while the multiple acts of criminal harassment must “seriously alarm[]” the targeted victim. Third, criminal harassment requires proof that the pattern of harassment “would cause a reasonable person to suffer substantial emotional distress,” but civil harassment has no comparable reasonable person element.

O’Brien v. Borowski, 461 Mass. 415, 420 (Mass. 2012)(emphasis supplied). Even if Ms. Nilan unreasonably interpreted Mr. Valenti’s words (there being no “reasonable person” standard in civil harassment protection), “they must be committed with ‘the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property,” and it would be outrageous to suggest that this was Mr. Valenti’s intent.

41

“True threats” must be objectively reasonable as a constitutional requirement and therefore statute suffers from overbreadth— O’Brien is wrong in this respect—the issue is reserved for U.S. Supreme Court.

As stated in O’Brien, “criminal harassment requires proof that the pattern of harassment would cause a reasonable person to suffer substantial emotional distress, but civil harassment has no comparable reasonable person element.” O’Brien at 420. And here lies in a constitutional problem with the statute itself. The “reasonable fear” requirement of a true threat is a constitutional requirement. “To justify suppression of free speech there must be reasonable ground to fear that serious evil will result if free speech is practiced.” Whitney v. Cal., 274 U.S. 357, 376 (1927)(Brandeis concurrence joined by Holmes). “In determining whether a statement is a ‘true threat,’ we have employed an objective test so that we will find a statement to constitute a ‘true threat’ ‘if ‘an ordinary reasonable recipient who is familiar with the context . . . would interpret [the statement] as a threat of injury.’‘ United States v. White, 670 F.3d 498, 507 (4th Cir. Va. 2012)(emphasis supplied); United States v Alaboud, 347 F.3d 1393,

42

1296-1297 (holding that determining just what is a true threat is determined by an “objective standard” that a “reasonable person would construe them as a serious expression of an intention to inflict bodily harm.”); United States v. White, 670 F.3d 498, 507 (4th Cir. Va. 2012)(“‘In determining whether a statement is a ‘true threat,’ we have employed an objective test so that we will find a statement to constitute a ‘true threat’ ‘if ‘an ordinary reasonable recipient who is familiar with the context . . . would interpret the statement as a threat of injury.”)

The O’Brien court attempts to “cure” this very real problem of compliance with “true threat” jurisprudence in First Amendment law that requires an objective inquiry as to whether a reasonable person would find the threats real. The O’Brien court argued that if “the speaker subjectively intends to communicate a threat,” as Massachusetts civil harassment protection statute requires, an objective reasonableness test may be obviated, reasoning that “[t]he requirement that the pattern of harassment in fact cause fear, intimidation, abuse, or damage to property satisfies the ‘true threat’ requirement that

the threat be regarded as a serious expression of

43

intent and not mere hyperbole.” O’Brien at 426. The O’Brien court then argues that an objective “reasonable person” standard is not required, because …

“the Legislature inserted the requirements that the defendant intend to cause fear, intimidation, abuse, or damage to property, and that the pattern of harassment actually cause fear, intimidation, abuse, or damage to property. We conclude that these requirements adequately ensure that protected speech will not be found to be civil harassment in violation of c. 258E.

There is no appreciable amount of protected speech where the speaker both intends to cause intimidation, abuse, damage to property, or fear of physical harm or property damage, and does in fact cause one of these alternatives.

. O’Brien at 418. It is supposed to be admitted that there are few cases where a person makes a threat that would not be reasonably interpreted as a real threat by a reasonable person, and wherein the person hearing the words nonetheless interprets the words as a threat. But this is to ignore the rules of evidence and the practicality of the fact finding process. Jurors can much more readily determine whether in a given context certain expression is objectively

44

reasonably interpreted as a threat because it does not require speculation as to what someone is thinking.

Allowing a court or jury to determine whether a reasonable person would find certain words or expression a real threat is an important prophylactic against unwarranted intrusion into the First Amendment—a prophylactic not afforded under the Massachusetts civil harassment protection statue as interpreted by the O’Brien court. Under an objective reasonableness test, one could simply inquire whether a reasonable person would find any given words or putative expression as a real threat to their person or property. It is a prophylactic in a way that trying to divine what an alleged perpetrator and alleged victim is thinking does not provide. While a situation gives insight as to what a person is thinking, fact finders are not mind readers. A test that does not rely just on determining the subjective intents of a speaker and listener but rather on what an objective person would reasonably interpret, as a practical matter, provides much greater protection for speech and expression of ideas. To simply argue that if someone subjectively intends to cause fear and the

putative victim subjectively is caused to fear, that

45

in such a scenario it is likely a reasonable person would likely interpret the speech or expression as fear (as the O’Brien court seems to have done), ignores the simple reality it is far easier to examine speech from the perspective of the objective reasonable person as opposed to being a mind reader.

Moreover, the O’Brien court does not find a single quote from a court that says the subjective intent of the accused perpetrator and putative victim will be an adequate substitute for an objective reasonableness inquiry into the legitimacy of a perceived threat. The O’Brien court is wrong and the statute suffers from overbreadth because for there to be a “true threat,” as a matter of Federal Constitutional law, there must be a threat that an objective reasonable person would find threatening to person or property. Merely divining what an accused perpetrator and a putative victim is thinking has never been held found to be a legitimate substitute for the objective, reasonable person test as required under the United States Constitution until O’Brien. This issue is preserved in case it ever goes to the United States Supreme Court.

46

It is supposed that the Massachusetts Supreme Court is the final word on the scope and protection of Article 16 of the Massachusetts Constitution and may dispense with the customary objective reasonableness determination of what constitutes a “true threat.” But the United States Supreme Court and numerous lower courts have stated that for there to be a “true threat,” there needs to an objective inquiry as to whether a reasonable person would find the threats to be actual threats to their person or property.

Ms. Nilan cannot claim that because she feared from third parties because of Mr. Valenti’s coverage of her case, that she is entitled to relief.

There appears to be an assertion that because others might have been inclined to threaten or harm Ms. Nilan, that Mr. Valenti must be stopped from his negative portrayals of her. One reason is that Valenti’s criticism of her and the system’s handling of her case has placed her under “continued emotional distress.” She states in her affidavit (p.2) that she “fears her safety” and that she believes that “recently related death threats . . . are related to

47

Mr. Valenti’s words.” Mr. Valenti has portrayed her in such an unfavorable manner, Ms. Nilan claims, that she “fears for [her] personal safety,”

“Restictions on public speech about a person . . . stand on a very different First Amendment footing from restrictions on unwanted speech to the person.” Eugene Volokh, ONE TO ONE SPEECH VS. ONE TO MANY SPEECH, CRIMINAL HARASSMENT LAWS, AND “CYBER-STALKING, (forthcoming Northwestern Law Review (20120).8

The argument Ms. Nilan advances is a frightening one. Any speech critical of others, especially speech highly critical of others for conduct that is usually thought to be odious, might lead others to have animus towards a particular individual that in turn might turn to violence or the threat of violence. This hardly is grounds to outlaw the speech. It is supposed that the print allegations regarding Michael Jackson’s alleged pedophilia (and getting away with it) might have lead a person to cause harm to Michael Jackson. Obviously, that could never be the basis for restraining orders aimed at individuals from being

8 This was retrieved on July 8, 2012 at http://www2.law.ucla.edu/volokh/crimharass.pdf 48

critical of Michael Jackson. As once stated by the United States Supreme Court:

Accordingly a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, supra, pp. 571-572, is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest. See Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252, 262; Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367, 373. There is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4-5 (1949). Were Ms. Nilan’s theory to be taken seriously, then accused murderer George Zimmerman should be able to seek injunctions against news agencies covering his case because their articles have promoted many to make

49

death threats against him.9 Former Beatle John Lennon was actually once murdered by a man who was in part motivated from a cover story he had read in the November 1980 Esquire Magazine, “JOHN LENNON’s PRIVATE LIFE: A madcap mystery tour” that portrayed Lennon as a recluse millionaire who in no way served the lofty anti-establishment causes of peace or love that he talked about so much as a Beatle—obviously, John Lennon would not have had grounds to get a restraining order against Esquire Magazine.

All writings critical of others has a tendency to make other think lower of the subject. Regarding matters where the subject is alleged to have done odious things, strong resentment may turn to animus, and animus can turn to violence. This cannot be a basis for banning speech.

Even, assuming arguendo, that Mr. Valenti has engaged in “fighting words” or “true threats,” the order is too broad and bans expression that is neither “true threats” or “fighting words” on Mr. Valenti’s blog.

9 As this brief is being written, Mr. Zimmerman is out on bail and staying in a “safe house” due to all the death threats that is no doubt related to the media coverage and the outrage it has caused.

50

It is ridiculous to conclude that Mr. Dan Valenti engaged in true threats or fighting words directed at Ms. Nilan. But assuming for moment that he engaged in fighting words or true threats, any relief a court might grant must be narrowly tailored to removing true threats or fighting words. A court has no right to order Mr. Valenti to take down his whole blog concerning matters that have to do with Ms. Nilan, even the speech that is protected speech and is not libelous, obscenity, a true threat, or fighting words.

“An order issued in the area of First Amendment rights must be couched in the narrowest terms that will accomplish the pin-pointed objective permitted by constitutional mandate.” Carroll v. Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175, 183 (1968). “In this sensitive field, the State may not employ means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved.” Id. at 393—394. “[T]he order must be tailored as precisely as possible to the exact needs of the case.” Id. at 394. At most, the court would have to identify the “true threats” and “fighting words,” and only order their removal—not “any and all information referring to the Plaintiff”

as it did in its June 27, 2012 order.

51

There is a constitutional right to publish truthful information about other individuals about an area of public concern.

Individuals have a constitutional right to publish truthful information about other individuals regarding a public concern. For instance, in The Florida Star v. B. J. F., 491 U.S. 524 (1989), a sexual assault victim sued a newspaper for publishing her name,10 when there was a statute that said a newspaper could not publish the name of a sexual assault victim. “B.J.F.” sued the Florida Star for negligently violating the statute. In an opinion of Justice Marshall, it was held that a Florida statute could not make a newspaper civilly liable for publishing the name. Marshall wrote that “The tension between the right which the First Amendment accords to a free press, on the one hand, and the protections which various statutes and common-law doctrines accord to personal privacy against the publication of truthful information, on the other, is a subject we have addressed several times in recent

10 The newspaper had accidently violated its own internal policy. 52

years.” Id. at 530. See also, Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975)(also invalidating a law against publishing the name of a rape victim).

It is to be admitted that the Florida Star court did rule, “We do not hold that truthful publication is automatically constitutionally protected, or that there is no zone of personal privacy within which the State may protect the individual from intrusion by the press . . .” Florida Star at 585. But the Florida Star court did hold:

We hold only that where a newspaper publishes truthful information which it has lawfully obtained, punishment may lawfully be imposed, if at all, only when narrowly tailored to a state interest of the highest order. Id.

In Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469, 496 (1975), another case that struck a statute that banned publication of the names of rape victims, it was held,

We are reluctant to embark on a course that would make public records generally available to the media but forbid their publication if offensive to the sensibilities of the supposed reasonable man. Such a rule would make it very difficult for the media to inform citizens about the public business and yet stay within the law. The rule would invite

53

timidity and self-censorship and very likely lead to the suppression of many items that would otherwise be published and that should be made available to the public.

However, when privacy interest clash with free speech interest, the United States Supreme Court has recently been more inclined to support free speech.

“As a general matter, state action to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy constitutional standards.”

Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001), quoting Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co., 443 U.S. 97, 103 (1979). In Bartiniki, a radio station played a tape of a conversation between a teachers union and a school board. Though the conversations were illegally recorded, the radio station did nothing illegally and had copies of the tapes.

This Court has repeatedly held that “if a newspaper lawfully obtains truthful information about a matter of public significance then state officials may not constitutionally punish publication of the information, absent a need . . . of the highest order.” [Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co., 443 U.S. 97, 103 (1979)]; see also Florida Star v. B. J. F., 491 U.S.

54

524 (1989); Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia, 435 U.S. 829 (1978).

Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001)(emphasis supplied). If it is well-settled law that newspapers have a protected right to publish truthful information that they did not unlawfully acquire about matters of public significance, it cannot be seriously argued that a blog on the Internet by a journalist does not enjoy similar protection.

In the instant case, Mr. Dan Valenti is publishing (1) truthful information that (2) is of a public concern. It matters not Ms. Nilan is otherwise a “private” individual and not a “public figure” in the First Amendment sense. Whether or not a person committed a hit and run and got away with it, whether or not she received favorable treatment from the courts or the District Attorney’s office because she is the daughter of the Chief of Probation at Berkshire Superior Court are all undeniably public concerns. Both the Massachusetts Constitution and the United States Constitution protect such speech.

55

The order constitutes an unconstitutional prior restraint and should not be continued.

Article 16 of the Massachusetts Constitution’s Declaration of Rights, (as modified Article 77), currently reads (emphasis supplied):

The liberty of the press is essential to the security of freedom in a state: it ought not, therefore, to be restrained in this commonwealth. The right of free speech shall not be abridged.

It is more than merely an irony that Mr. Valenti’s speech—that of a journalist—has been restricted in a restraining order given the plain words of Article 16 that “the liberty of the press . . . ought not to be restrained”; it is a plain violation of Article 16.

Any government order that restricts or prohibits speech prior to its publication constitutes a prior restraint.” Rotunda and Nowak, Treaties on Constitutional Law Sec. 20.16(h) p. 114 (Fourth Edition). “The term ‘prior restraint’ is used ‘to describe administrative and judicial orders forbidding certain communications when issued in advance of the time that such communications are to occur.’”

56

Alexander v. United States, 509 U.S. 544, 550 (1993)(emphasis added by Alexander court), quoting M. Nimmer, Nimmer on Freedom of Speech § 4.03, p. 4-14 (1984).

Judge Bethzaida Sanabria-Vega issued a temporary order of harassment prevention pursuant to Mass. Gen. L. c. 258E §5 and “ordered [Mr. Valenti] to remove any and all information referring to the Plaintiff [Ms. Nilan] from any and all websites, blogs, etc.” This is a prior restraint in the sense that court did not review the contents of the website before entering the injunction and issues an order ex parte. Moreover, it is a prior restraint in the sense that Mr. Valenti is not allowed even to publish new articles about Ms. Nilan, including any reference to this case, because Ms. Nilan cannot be mentioned by name. This is classically a prior restraint because the communication is being forbidden before it occurs.

“Prior restraint” is often contrasted with “subsequent punishment.” “Courts and commentators define prior restraint as a judicial order or administrative system that restricts speech, rather than merely punishing it after the fact.” Mortgage

Specialists v. Implode-Explode Heavy Indus., 999 A.2d 57

184, 194 (N.H. 2010). “The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.” Near v. Minn., 283 U.S. 697, 713-714 (1931), quoting 4 Blackstone Commentaries 151, 152.

The United States Supreme Court has stated that “[t]emporary restraining orders and permanent injunctions — i.e., court orders that actually forbid speech activities — are classic examples of prior restraints.” Alexander v. United States, 509 U.S. 544, 550 (1993). Of course, requesting a court to issue a restraining order asking a defendant to “remove any all information referring to the Plaintiff from any all websites, blogs, etc.” as this court did on June 27, 2012 constitutes a classic example of a prior restraint vis-à-vis its restraint material Mr. Valenti

58

has yet to publish on his website or through other manner.