Don’t Look Now, but the Past is Gaining on Us. Problem is, it’s a race many won’t win.

By DAN VALENTI

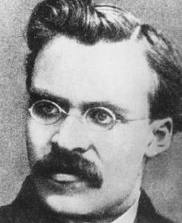

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, perhaps the most misunderstood moralist of all time, had an intriguing and compelling look at the nature of history. As he often does, he uses concrete images to convey deep truths.

In “The Uses and Disadvantages of History,” Nietzsche discusses the nature of time by placing us in a field, where a bunch of little cows are grazing on the grass, blissfully unaware of not only the moment but of any moment. A man walks up to the cows and asks what it feels like to be able to live constantly in union of thought, intent, and action — what we call being “in the moment.” He wants one of them to tell him about their apparent happiness and lack of worry.

The cows hear the question, but before one can reply, “I don’t know what you mean,” it has passed into a new moment where the reply, now forgotten, is as meaningless and unapparent as the original question. The cow, without pretense or any manipulation, lives in the forever “now,” which can be understood as one definition of sacredness.

Everywhere but “Now.”

The man who asks the cow what it’s like, however, is wrapped up by the constraints of the past that was and the anxieties of the future that will be. He’s everywhere but in “now.” The man’s experience of “it was” changes everything for him. The “it was” of his past and of the past in general, Nietzsche says, is the ghost that haunts every succession of the man’s life in time. There is no way he can escape “it was.”

The man who asks the cow what it’s like, however, is wrapped up by the constraints of the past that was and the anxieties of the future that will be. He’s everywhere but in “now.” The man’s experience of “it was” changes everything for him. The “it was” of his past and of the past in general, Nietzsche says, is the ghost that haunts every succession of the man’s life in time. There is no way he can escape “it was.”

Think of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous ending to what is THE PLANET’s nomination as the Great American Novel: “And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne ceaselessly into the past.” No matter what we do, where we run, or how much we distract ourselves, we can’t escape this chronological ghost. Thus, our histories haunt us. We experience individually and culturally the pain, hurt, and suffering of what was, and that is often what prevents us in the elusive present from understanding what has happened to us.

Techno Now

Ours, of course, is a shallow age where technology has captured everyone with its own version of “now.” Computers have given us capabilities beyond our maturity level (or haven’t you noticed the overwhelming irresponsible uses of the internet such as gambling, pornography, and out-of-control shopping of goods we don’t need). In the smallest cyber unit of time, billions of calculations can be made.

Computer programs give one person enormous capabilities, which industry masks with the word “productivity.” That is code for one person now being able to do the work of four. You see it in newsrooms, banks, factories, and practically all commercial transaction: the impersonal residue when you take people out of our exchanges and substitute recordings, touch screens, keypads, and photoluminescent blips. That four-for-one productivity means that three people have lost their job and the remaining one carries four times the responsibility, often at the same salary.

They are the lucky ones. The true victims of this new age in the experience of time and the technological expansion of capability its proper handling are kids in middle school and younger, up to the age of reason (seven). At least the rest of us to some extent or another know of a more visceral and less virtual time. We can remember picking up a land-line telephone and always reaching a human being if the line wasn’t busy.

We can remember when lift-off tape was the latest advance in “work processing,” on a new gadget called an electronic typewriter (the first time I used an IBM Selectric typewriter, I thought I had experienced the future).

The Monster Always Returns to Destroy its Maker

In fact, many of us know full well how well life can function without any personal computers. Young kids do not know this. They only know a world where they are constantly plugged in, online, thumbing brainless messages on textpads, and the like. In this cyberworld, the “it was” has no meaning. Unlike with animals, however, this provides no advantage for humans.

Last week Dr. Alan Gold and I got into a conversation about this topic. He made an excellent point in saying that the children he has observed have no interest in anything except themselves. I have talked with my colleagues on the faculty at Berkshire Community College, and they note that the traditional freshman each year comes into higher education with a noticeable reduction in intellectual curiosity.

Taconic High School Principal John Vosburgh, who is in his second year, has told us as much of the current wave of middle schoolers. Vosburgh should know. He spent the previous nine years assigned to teaching and administrative work at the middle school level.

“I Have Seen the Future. It Be Us.”

He told THE PLANET that if you think this problem of the technocratization of youth is bad in high school (with its resultant discipline, attention, and adult supervision issues), wait until today’s middle schoolers graduate to 9th and 10th grade. Vosburgh said the schools don’t have a clue how their going to teach this new young set, a group of experimental creatures with the potential for havoc of Frankenstein’s monster.

No, they won’t kill a burgomaster. They won’t terrorize the village with physical mayhem. They just won’t be equipped — academically, socially, or spiritually — to handle adulthood. They will have Google and an online porn shop in their palms, but will they be able to handle setbacks, deal with disappointment, learn that success comes from hard work, determination, persistence, and infinite patience? What will they do when they find that their problems won’t be solved with the click of a mouse?

This phenomenon turned up in a report released today that a full one third of 8th graders who attend urban public school districts statewide are in danger of dropping out before graduation. What will the choice be: a lowering of standards that will place no requirements on graduates, or a maintenance or even boosting of standards and seeing massive numbers of dropouts?

Chuck ‘It Was.’ Choke on ‘Why Me’?

Like the cow, these kids won’t have “it was.” They will have “what happened?” and “Why me?” That is much worse, for it shall lock many of them into perpetual babyhood. They will be limited in coming to a fresh and honest evaluation of life, of the “it was.” Computers won’t help them. They will reach adulthood almost as a type of Alzheimer patients, as if the constant effects of being wired in created a technological mutant of the disease that produces the exact opposite effect: the inability to achieve forgetfulness. Since they are humans and not sacred animals, they will eventually need the past.

The past won’t be there for them in a way that can lead to healing and reconciliation.