**UPDATED** A SUZUKI SCROOGE: BTF’s HILL TAKES DICKENS’ “CHRISTMAS CAROL” TO THE TOP

A Berkshire Theatre Festival production of A CHRISTMAS CAROL by Charles Dickens. Adapted by Eric Hill. Directed by Eric Hill and E.Gray Simons. Starring Eric Hill as Ebenezer Scrooge. Plays Dec. 11-30, 2010, at the Unicorn Theater on the BTF campus in Stockbridge, Mass. Go to the BTF website for remaining performances and times (www.berkshiretheatre.org.). Tickets are $20 for adults, $15 for children and students. Group discounts available. Box office phone is 413-298-5576 x33.

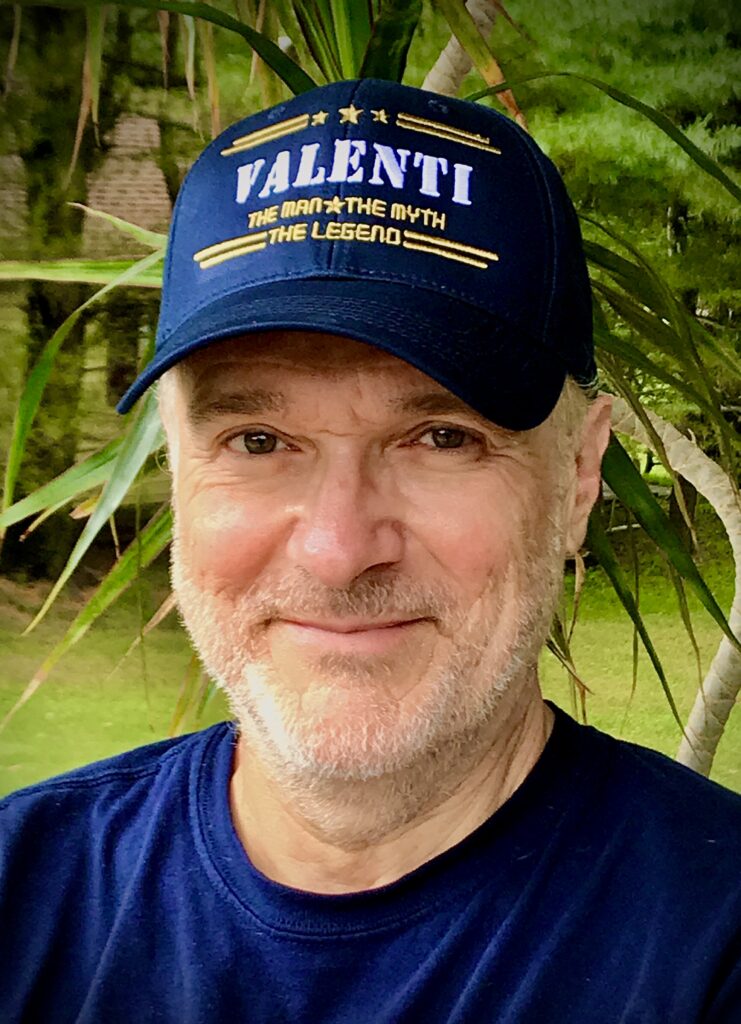

REVIEW BY DAN VALENTI

Eric Hill’s adaptation of the Charles Dickens classic, “A Christmas Carol,” seems to have Stockbridge solidly in mind. It does this in tone, personnel, setting, and above all, near perfection honed after four years and being applied into the fifth.

Dickens’ Victorian tale of redemption has played countless times on countless stages, to say nothing of the many film adaptations (see sidebar at the end: “The Screen’s Top 5 Scrooges”). Having seen this play in a number of different theaters and in many film adaptations, THE PLANET loves the intimate size of the Berkshire Theatre Festival production in the cozy confines of the Unicorn Theater, 125 seats large.

Size matters, and the Unicorn suits the nostalgic intimacy of “A Christmas Carol” to a Tiny Tim. There are no dazzling ghost entrances, just simple, well-staged walk ons. There are no rising and lowering sets, just ample use of a smallish stage that must at times accommodate 27 people. There is no attempt to sheepishly follow the conventions of more well-known adaptations, just Hill’s authentic homage to the narrative “sacredness” of one of Dickens’ master works.

The fact that he had limited resources and had to cast amateurs provide no hindrance at all. It is also true that for a community production such as this, the audience comes with an unusual amount of forgiveness at what it might see. Make no mistake, however, that under Hill’s keen eye, there is not a false note rung. Hill’s tight editing of the story is done with adroit selectivity, creating the impression that he was and is a reader who knows the difference between the “life” of words on a page (coming to life in the reader’s mind) and the “life” of words as they are acted on stage.

Dickens’ 30,000-word tale, “A Christmas Carol” is the most flawless of his narratives, edging “Great Expectations” among the writer’s 27 novels. It was the power of this 1843 work that it singlehandedly restored brightness to Christmas in Victorian England after a long, somber period of lost festivity. Dickens drew heavily from the misery he has personally witnessed as a boy. A falling out with his publisher caused Dickens to self-publish “A Christmas Carol.” How much did he love this work? He spared no expense in the book’s production yet sold it for less than cost. It became and immediate sensation, selling out its 6,000 copies immediately.

An Economy of Scale

“A Christmas Carol” attracts addaptation the way WikiLeaks attracts the government police, mainly because of the tightness in the telling. Dickens periodically went back to his work in subsequent editions, paring, changing, until he had the current version. An adaptor/director like Hill thus has a partner editor in Dickens himself. The author could self-edit ruthlessly, and he has removed most of the chaff.

This creates a set of problems of a different sort, though, for adaptation. With so little to cut, the cuts can be agonizing … and hollow. Having to scale down the production could have led to trouble, although it’s hard to imagine anyone truly fouling up Dickens’ flawless story. Hill embraces the economy of scale, imagining mid-19th-century London with enough hospitality to appear homelike and enough hardness to seem cruel.

Hill’s adaptation has humor, warmth, the more than an edge of terror, particularly in the red-and-black-lit scene where Scrooge sees his name chiseled on to a gravestone.

Even at that, the play, in this condensed version, resonates with all of the intention of the full work, including an eye-to-eye look at the large issue of morality. Dickens was not a mere entertainer. He confronted with words the appalling social inconsistencies of the western world (London standing in) on the brink of the Industrial Revolution. That sea change made fortunes for some but left the many in abject misery. The homeless lived in alleys and gutters. The mentally ill were locked up and treated like animals. Widows and orphans were left to fend for themselves. Industrialization moved populations from the clean-air and room of the countryside into the toxic fumes of overcrowded slums.

Are we are brothers’ keepers? If so, why? If not, why not? What are the obligations charity and mercy impose on the well off to the less fortunate? Dickens wasn’t afraid to look, and in doing so, to cast his verdict in a decidedly Christian context — secular Christianity, if you will. There are no “Happy Holidays” here but a firm “Merry Christmas” and a tip of the top hat to “the one who made blind men see and the lame walk.” What would Jesus do? Why, he’d buy a ticket and find a seat at the Unicorn.

Even Scrooge’s “Bah, humbug” contains epic more character. A good man has gone bad. Hill utters this line in a way that this reviewer has never seen. It isn’t a nasty growl. It’s an almost verbal sillywalk. When Hill as Scrooge “humbugs,” we hear a glint of playfulness trying (ultimately failing) to come out. It takes getting used to, but it works. Hill’s Scrooge, even at his nastiest, has a hint of goodness around the eyes, as if the old man has even unconscious “self care” to portend his own redemption.

Hill engages Dickens in a pas de deux, letting Dickens take the lead. He follows the author’s tactic of exemplification, illustrating the story’s abstract, intractable social ills (poverty, rampant ignorance, want) through the events and people circulating about the life of the cold, miserly Ebeneezer Scrooge, wonderfully portrayed by Hill. The moral: It’s never too late to change. The cast includes clerk Bob Cratchit (Mark Rosenthal), Scrooge’s late partner Jacob Marley (E. Gray Simons III), and his nephew, Fred (Jesse Hinson). Hill and Simons co-directed.

Three Tales in One, All Beloved

“A Christmas Carol” is simultaneously the world’s favorite ghost, Christmas, and time-travel story. It focuses on relationships — the ones Scrooge had, lost, missed, and now seems doomed to endure in a relentlessly bleak and hopeless future. Consequently, the ensemble in this fast-paced 90-minute show steps forward eagerly into more prominence that it’s usually given in other versions. The youthful group has fun embracing the opportunity.

Four ghosts take Scrooge back to the past, his past. They are Scrooge’s former partner, Jacob Marley and three Time Phantoms — the Ghosts of Christmas Past (a

shimmering Samantha Richert), Present (Ralph Petillo, the utility man of the production), and Future (Kori Alston, who with prosthesis plays as tall as Manute Bol). The ghosts show Scrooge the lost opportunities of his past, reveal the unfolding present, and provide a frightening glimpse into a future that, if not amended, will cast Scrooge six feet under with his soul at risk.

Hill as Scrooge generously steps back, literally to the stage’s background edges in many scenes, as the ensemble transforms Dickens into engaging action. Hill’s inhabits Scrooge full of Suzuki-inspired movement, lowering his center of gravity and slowing his movements to suggest the heaviness that weighs him down. Hill shows in his body Scrooge’s conflict. Dickens’ diamond dialogue (“Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”) finds the right setting. [NOTE: Suzuki is a method of body training that brings intense and exaggerated physicality into an actor’s movements.]

From the opening song to the closing carol, the chorus of “A Christmas Carol” populates the Unicorn stage with a delightful mix of talent, youth, energy, and engagement that, if it were a drink, would lead us all Wassailing, quite under the happy influence, thank you. We identify the chorus by name the way the New England Patriots get introduced at the Super Bowl: as a team — Alston, Emily Cooper, Alee Danyluk (who also plays a mean fiddle), Emma Foley, Amy Kane, Hanna Koczela, Rebecca Leigh, Michelena Mastrianni, Anna Grace Nimmo, McKenna Powell, Daniel Garrity, Caroline Fairweather, Abby Schilling, Rufus Taylor, Marcella Tanuta, Sophia Tenuta, Kori Alston, Lindsay Belair, and Emelyn Theriault. Henry Taylor is Tiny Tim, as adorable a little boy as one could envision for the part.

Teamwork Overcomes All

This is not a big-budget production, and the staff pulls out many clever stops to create the proper atmosphere for “A Christmas Carol.” When Scrooge goes home in the cold, damp London streets, we feel the chill of the Jack-the-Ripper byways. There are no cobblestones to be seen but in the mind’s eye. When Scrooge visits by apparition the home of his nephew Fred, we feel the warmth of people and hearth. A warm fire emanates from the fireplace, quite the contrast with Scrooge’s pitiful lone candle that battles the darkness in the man’s echoey chambers.

Experience is showing here, folks, with scenic designer Carl Sprague hitting us with a palette of gray, black, brick, and brown dotted with spots of color and light: a candle’s glow, a fireplace’s shimmer, and the light as it peeks through the foreboding London skyline the windows of buildings.

The lighting — everything from a disco dance-floor sparkle-ball to solitary spotlights — serves well by NOT telling us how to feel but by hinting. For instance, when Scrooge tries to blow out his lone candle prior to seeing Marley’s ghost, it keeps coming back on. The effect is both clever and informative. We see Scrooge trying to come to terms with the impossible and failing. He shows his anger, frustration, and his refusal to believe his own senses. Clearly, this is a man imperially out of touch with his life. Matthew Adelson’s lighting scheme works well with Sprague’s set.

Hill and Simons brings the precision teamwork of set, lighting, costumes (Jessica Risser-Milne), sound (J. Hagenbuckle), and choreography (Isadora Wolfe) to the actors, infecting them with a sense of, for want of a better term, what we can call “urgent

Ralph Petillo at the Ghost of Christmas Present: The pipes are OK but he needs to cast a bigger shadow.

fun.” This means performers taking their work seriously but not themselves. We see this in Petillo, who in his four roles (Solicitor, Ghost of Christmas Present, Old Fezziwig, and Man of Business). He pulls off his duties well, except for the ghost. He’s just not big enough. The Ghost of Christmas Present needs to be a larger-than -life with basso profundo pouring out of every centimeter. Petillo’s got the pipes but not the presence. A big, fat man would work, or Petillo in a fat man’s suit.

Kim Taylor plays Mrs. Cratchit with sensitivity and grace, as a woman whose personal moral conscience even bids her to follow her husband’s wishes in toasting Scrooge, a man she loathes for making her husband’s life miserable. Mark Rosenthal plays a serviceable Cratchit, delivering an even performance. He looks a tad young, however, when he comes home and plays patriarch to his family. He needs more makeup to add a few years. In acting, looking the part brings you halfway home.

Other performers include Michael Brahce as the Narrator, Sam Gilliam as Young Scrooge, Gail Ryan as Mrs. Fezziwig, and Christopher-Michael Vecchia in a several small role

With five years in the making, the BTF’s “A Christmas Carol” has gone beyond one-shot deal, morphing into veritable Tradition. It has become as “necessary” to Christmas in the Berkshires and especially Stockbridge as a warm bowl of punch and presents under the tree.

Of all the versions of “A Christmas Carol” that you may enjoy during this festive time, the BTF’s is the one THE PLANET must label “can’t miss.”

Ninety minutes of pure enjoyment — can you think of a better Christmas present than that?

SIDEBAR

THE TOP 5 FILM ADAPTATIONS OF “A CHRISTMAS CAROL”

1. The George C. Scott version (1984). Never before or since has Scrooge’s character become a living growl. Brilliant. Scott’s rasp makes barbwire of the miser’s dialogue, and his tender whispers deliver every ounce of the redeemed man’s happiness.

2. Alastair Sim version (1951). Scrooge at his hard-hearted best. The black-and-white shows the grime of London and the darkness of Scrooge’s life in color, as it were.

3. The Albert Finney musical version. In tune all the way.

4. Mr. Magoo’s version (1962). My favorite as a kid. Jim Backus, great songs, and one of the best limited-animation productions ever made. What’s not to dig?

5. All the others. There isn’t a bad version of this tale. You couldn’t screw up “A Christmas Carol” if you tried. The writer William Makepeace Thackerry, noted for his savage reviews, called this the best story ever plotted. THE PLANET says it’s the equivalent of a pitcher throwing a perfect game.

Saw this with a friend on Saturday. Fun and enjoyable. What a great job the kids did.Thanks for the review how do you remember all of that? PS we saw you Dan with your wife and also James Taylor. It was like a Hollywood opening for us!

Thank you for covering this. We enjoyed the play very much. I shall never tire of “A Christmas Carol.”

A beautiful show. See it.